Steve Clark drives hometown revival in ways large and small.

By Dwain Hebda

The looming Fort Smith murals painted on the side of OK Foods’ silos are as captivating a piece of public art as can be found anywhere in Arkansas. Soaring over the landscape on one edge of downtown, the black-and-gray “American Heroes” depicts three individuals in stunning detail: Kristina, a young business owner, and Ed, a Navajo man active in the Lawbreakers and Peacemakers reenactment group, flank one square silo, while Gene “Beck” Beckham, a World War II veteran and 70-year OK Foods employee, is portrayed on the other.

As with all great artwork, the key to “American Heroes” is the angle of perspective of the viewer. In this case, the angle of the subjects’ view is important as well. Ed’s gaze is downward as if taking stock of what’s behind him; Kristina looks out steady and confident to her right, and Gene’s eyes aim skyward. It’s an apt representation of life, be it individual or in the collective, seen in triptych: acknowledgement of the past, focus on the present and a glimpse of the future.

“Placemaking has been an effective catalyst for revitalization and renewal throughout fort smith.”

If Fort Smith entrepreneur Steve Clark’s work in reviving his longtime hometown needed an illustration, many would do, but none would be as fitting as Guido van Helten’s monochrome masterpiece. Clark, a highly successful entrepreneur that claims Fort Smith as his adopted hometown, has spearheaded the drive to reinvigorate the city’s core through public art, repurposed buildings and fresh thinking.

“Anything we can do to make it easy for people to live, work and play and then make it desirable for developers, through any number of plans, to develop should be top of mind for those of us working on downtown and for the city at large,” Clark said.

Clark’s love affair with the city dates back to his childhood where trips to Fort Smith would form a blueprint for what he would attempt to resuscitate later in his adult life.

“I graduated from Roland, Oklahoma, High School in Sequoyah County and have had a bit of a romantic relationship with Fort Smith,” Clark said. “You leave Roland, you drive through the bottoms where it was agriculture and then you would get to the Arkansas River where you’d cross the bridge. Coming off the bridge you’d be coming into this really picturesque downtown. There was kind of this transition from rural agricultural to urban downtown and I was always captivated by it, whether it was lit up for Christmas and the holidays or just bustling with activity.”

After earning a bachelor’s degree in finance from the University of Arkansas in 1986, Clark lived in Little Rock for a spell before returning to Fort Smith in his 30s. He founded Propak, a provider of logistics, transportation and supply chain management solutions, growing the company to thousands of employees, including dozens in its downtown Fort Smith headquarters. He also founded Rockfish, a digital media company, and while growing both companies he couldn’t help but notice how the vitality of his businesses stood in sharp contrast to the generally stagnant state of the community he called home.

“[Industry] was still going, but you could certainly feel that there was beginning to be a bit of transition,” he said. “And then when Whirlpool closed their big plant here [in 2012], it took us quite a while to see that not only is Fort Smith changing, but the economy at large is changing. I feel like we went through maybe a 10-year stretch where I’m not sure we really knew what to do.

“Fort Smith is a city with fantastic bones, but it was a very strong manufacturing city, and when Whirlpool went away I think we were focused on trying to do what we had always done. Even though we have a fantastic chamber and fantastic leadership at the chamber, what we as a city had been set up to do was changing.”

Rockfish sold in 2016 and Propak in 2022 and today Clark remains employed by the latter in addition to mapping, out other entrepreneurial pursuits. That, and his ongoing work to help Fort Smith reimagine itself and its place in the global marketplace.

South Ninth Street mural.

“We can never lose sight of the fact that we’re in a global fight for the maintenance of jobs and the attraction of new jobs and the education to prepare us for the jobs of the coming generation, which is changing quickly,” Clark said.

It’s not the first time the city has had to radically change course to keep up with the changing times. Steeped in frontier lore, Fort Smith was founded in 1817 as a military outpost, with a small settlement sprouting up around it. The military would be an important economic driver in some form for the next 200-plus years, thanks to the establishment of Fort Chaffee in the 1940s, but dwindled until the U.S. Army base transitioned to an Arkansas National Guard training facility in the 1990s.

Economic diversification came via manufacturing that took advantage of the river, railroad and later highway transport that was available. Like the military, manufacturing remains an important sector, though not nearly what it once was. The loss of Whirlpool and its 900 jobs sent shockwaves through the local economy, and a period of malaise set in as the city struggled to reimagine itself.

Into this breach stepped community visionaries, Clark among them, who lent critical leadership to the efforts of the city to regain its momentum.

“You can’t really explain the why, other than you kind of wake up and realize there’s no economic cavalry coming. You fight a little harder if you think you’re on your own,” Clark said of his motivation to get involved. “And let’s face it: The economy has changed so dramatically and shifted from local to regional to state to national and then global that the things we’re doing, or trying to do here, are literally the minimum price of participation.

“I think that’s kind of where I landed, that it was not realistic to think a municipality or bureaucratic organization could have that kind of perspective or vision. You can’t even be upset about it. They’re simply not set up for it. It takes a lot of the same entrepreneurial tenets that exist in business or commerce and need to be applied on a larger scale for civic return.”

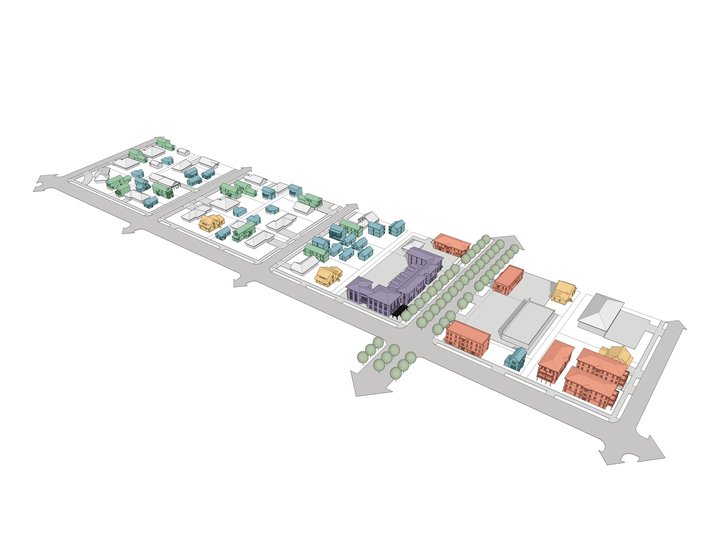

Clark and his allies in this effort approached the problem from a wholly unique angle. Whereas traditional strategies revolved around cheap land parcels or available warehousing, the new approach called for something called placemaking, investing in community amenities that enhanced quality of life to lure employers and attract and retain workforce.

A bold reassigning of both chicken and egg in the economic development equation, placemaking has been an effective catalyst for revitalization and renewal throughout Fort Smith ever since, particularly downtown.

At 70 S. Seventh St.

Clark’s fingerprints on this process are most clearly visible through 64.6 Downtown, a nonprofit committed to creating vibrant spaces through business development, arts and culture, special events and projects. That group spawned The Unexpected, which is responsible for much of the larger downtown artwork that peeks out seemingly everywhere today.

Since 2015, The Unexpected has steadily helped craft the city’s new image, inspiring countless other communities statewide to follow suit in public art. But as with all radical new ideas, the early years of the effort ran contrary to many residents’ tastes.

“I remember telling people I may literally be forced to move because of this, because there was a huge outcry of people who did not like the idea of art on historic buildings,” Clark said. “I was standing in front of a broken, empty building that a beautiful mural was going on and a woman was standing there just shaking her head. I go, ‘What do you think?’ She said, ‘I don’t like it.’ I said, ‘What do you not like?’ She said, ‘It’s not our history.’ I said, ‘But frankly, neither are empty buildings and broken glass.’

“I wanted to be empathetic because what she was saying was ‘It’s not how I would do it.’ Fort Smith was stuck in her mind in a very particular, sentimental way. But the flipside of that is, as I told her, I love our history, I just don’t want to live in it. It’s important to remind people that this is who we are and then to act on that to make people see downtown differently than they’ve been used to seeing it.”

In the eight years since The Unexpected debuted, others in the city have adopted its audacious mindset, launching revamped living and gathering spaces, establishing festivals and birthing attractions including the crowning achievement of the U.S. Marshals Museum, slated to open this summer. As each new dream comes online it spawns something else, with the museum promising to be the biggest incubator of all.

“[The museum] has been a long-term process. I have been involved with it as a donor throughout,” Clark said. “Anytime you can have a federal museum in your city, especially one of the magnitude of U.S. Marshals, it’s a big thing. It would be impossible to overestimate the potential value.

“We have the largest undeveloped riverfront, I think, of any mid-sized city in the country. I think that becomes the first big ornament on that tree, on the river. The way I look at it is it puts us in a tier of cities that take themselves seriously and take their citizens seriously by doing the things they need to do for continued growth in the future.”

As commanding and ambitious as art such as “American Heroes” is, it’s not the only thing that catches the eye in downtown Fort Smith these days. Public art abounds in large, vibrant murals on brick and board and via street pieces that range from bronze effigy to whimsical junk sculpture. There’s also a certain art to the way commercial buildings have been refreshed, of the music and the food aromas that float on the breeze in summertime. All of which Clark has played a role in nurturing, either directly or indirectly, as part of a long quest to help the city rediscover itself.

Steve Clark

“Before The Unexpected, downtown just kind of was what downtown was. It was where the courthouse was, it had a lot of history,” Clark said. “Now you’ve got people wanting to bring their families downtown to see the arts. You have greater civic participation, greater attendance at the city director meetings, more people willing to say this is what we need, this is what we want.

“It’s not just about attracting jobs; it’s about keeping jobs, it’s about making Fort Smith a place where ultimately people don’t want to leave. That really has to be the first goal. And I think that’s what we’re doing. I think we’re seeing ourselves, maybe for the first time in a long time, as a place where people want to stay.”

Talking about such achievements lends a crackling energy to Clark’s voice. There’s still work to be done to help solidify the residential and commercial amenities downtown, but there’s an undeniable air of optimism in Fort Smith, to his great delight and satisfaction.

“So many things in history are not quite explainable other than there seems to be a rising up of people who say, ‘This isn’t necessarily the type of city that we want right now,’ so what does the city that we do want look like?” Clark said.

“People ask me why do this? The answer is, because this is the type of city I want to live in, that’s why. A city that can appreciate the arts, a city that can appreciate its historicity but not necessarily be stuck in it.”