Fayetteville looks to ADUs, pre-approved designs as solutions.

BY JONATHAN CURTH

A crisis seems like the perfect time to suspend, bend or even break the rules. Natural disasters often see curfews imposed or martial law declared. Military conflicts lead to national governments appropriating material and equipment. Often these efforts are successful in achieving their stated intent. Perhaps just as frequently, though, the tools employed to address a crisis have unintended, long-term negative consequences.

“For local governments, among the more pervasive of issues arising to the level of crisis are housing availability and affordability. Once the problem of the United States’ more prominent coastal markets, ballooning housing prices are now found nationwide, including in parts of Arkansas. ”

Notably, Northwest Arkansas’s housing market continues to stand out for its growth in both construction and prices. While Arkansas overall retains one of the lowest median home values in the country, the cities of Benton and Washington counties are experiencing dramatic market change.

Fayetteville, the largest city in the region and the second-largest city in Arkansas, is looking at ways to address its housing crisis with changes to building regulations and permitting times and other moves. The impetus was the doubling of the average price of housing over the last eight years.

In 2012, the average home price in Washington County’s county seat was $200,000, according to a Skyline Report performed by University of Arkansas researchers. In 2022, the report found, the average price was $400,000. Over a longer period, from 2010 to 2022, Fayetteville’s multifamily housing vacancy fell from approximately 15% to 1%. Without a commensurate increase in income, residents are relocating, being displaced or dedicating ever-greater proportions of their income to rents and mortgages.

Fayetteville in particular is further challenged by an additional factor: It is home to Arkansas’s largest university. While the University of Arkansas is an asset to Fayetteville, the region and the state, its growth has strained the local housing market. After expanding by approximately 1,000 students annually for 10 years before plateauing at approximately 27,000 in 2019, by 2022 enrollment had grown to 31,000. The immediate impact of this was an inability to house all the students who wished to live on campus. To accommodate the expanded enrollment, the university signed contracts for almost 1,000 bedrooms off campus in private, multifamily developments. While the influx of students undoubtedly benefits aspects of the local economy, it also impacts housing options for nonstudents.

In this climate of growing housing costs and dwindling availability, there is a strong temptation for elected leaders to increase home construction at any cost. Zoning codes that once assured predictability are recognized as midwives for land-hungry, low-density development patterns. Subdivision connectivity standards adopted as best practices now reveal each street stub-out to be a lost house. Areas of potential natural hazard, like slopes and floodplains, appear as unexplored greenfield sites.

In Fayetteville, a critical approach has been taken, but not necessarily at the cost of urban design and planning. Instead of repealing ordinances or letting ineffective ones remain, many are revisited and amended after validation against planning goals. Rather than short-circuiting a permitting process, it is assessed and often streamlined. When anticipated outcomes are not realized, different approaches are explored. Instances of each follow from Fayetteville’s years-old steps toward a larger, quality and more diverse housing stock.

Among the steps that have garnered Fayetteville regional and national attention is its evolving regulation on accessory dwelling units (ADUs). In recognition of a newly adopted “attainable housing” goal in 2005, planners presented the city council several tools to promote housing options. Among these was a means to allow existing homeowners to add housing to their property. Like many cities, much of Fayetteville’s land use is dedicated to areas of single-family homes that are unlikely to be redeveloped and present little opportunity for more housing. A solution was an old one found in many areas of Fayetteville and nationwide: ADUs. Also known as carriage houses, mother-in-law suites and by a host of other names, ADUs represent a rare opportunity to add incremental, small-scale housing to existing neighborhoods while also empowering homeowners with a means of supplementing their income with an on-site rental.

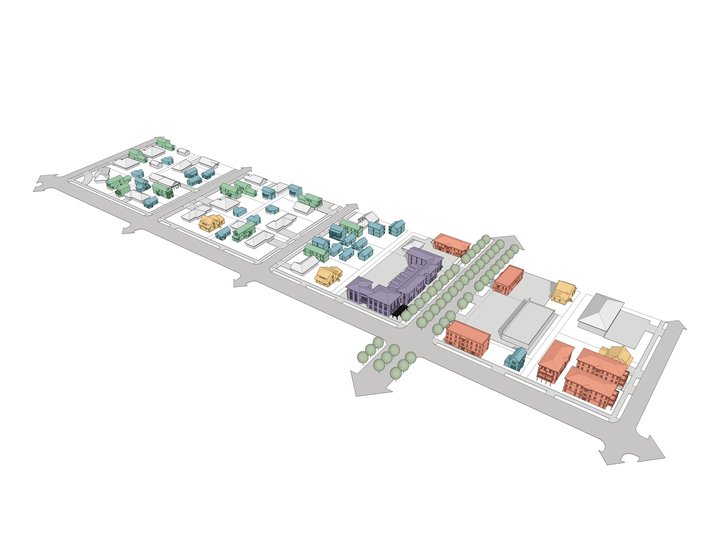

Traditional neighborhood with incremental development.

Fayetteville’s city council recognized and continues to recognize the value that ADUs represent. With an initial ordinance adoption in 2008 to permit ADUs anywhere single-family homes are allowed, the council has since amended the ordinance three times to broaden allowances and reduce regulation of ADUs. Key barriers to remove were a standard for separate utility metering, a deed restriction requirement that mandated that a homeowner live in the main house on a property or the ADU, and numerous prescriptive design standards. With these “poison pills” eliminated, limits on ADU sizes and the number of permitted ADUs per property were increased, and ADUs were permitted to be built in association with duplexes. Many other changes were made, with the net effect being a dramatic increase in ADU permitting, albeit from a low starting point. Where Fayetteville issued between one and three ADU permits in the late 2000s, 16 were approved for construction in 2022. In a similar vein, Fayetteville recognized that its goal to encourage more diverse housing options was being confounded by legacy ordinances that pushed developers toward single- and two-family dwellings or large apartments. Given the less stringent standards that applied to detached houses and duplexes, it is perhaps unsurprising that many developers chose this construction type despite any community need for townhomes, three and fourplexes, cottage courts and a wide range of other housing types now commonly known as the “missing middle.” On the other end of the spectrum, to justify the expense of engineering and design, a developer contemplating anything beyond a detached house or duplex had to build many, many more units.

Around the same time that the consequences of these development standards were becoming widely understood, Fayetteville and the University of Arkansas grew rapidly and the city experienced multiple flooding events. Students no longer able to be housed on campus and new residents entered Fayetteville in larger numbers, often housed in large footprint single- and two-family homes with associated driveways and other hard surfaces without accounting for run-off. Although a 6,000-square-foot duplex required no accommodation for stormwater capture, a 3,000-square-foot fourplex did. Where smaller units in greater numbers may have been what Fayetteville needed, ordinances continued to push the market toward the path of least resistance.

This changed in 2021 with one of the largest amendments to Fayetteville’s development code in years. With Planning Commission and development community input, staff proposed that development standards and project categories be based on new imperviousness instead of housing type. That means the amount of new concrete, asphalt, rooftop and other areas that prevent rainwater infiltration is the new standard. If a project can minimize these impervious surfaces, it is eligible for streamlined approval. Fayetteville’s city council adopted the new standards, and they are in practice today, albeit with insufficient time to evaluate effectiveness.

Regulations can hamper the supply of affordable housing: For every residential project that is denied or becomes infeasible due to regulation, labor shortages, building material prices or public opposition, those unrealized housing units contribute to higher housing costs. Although it is overly reductive to assert that Arkansas, Northwest Arkansas and Fayetteville can build their way out of our housing crisis, it is irresponsible to dismiss the upward pressure on home prices and rents when more residents compete for fewer homes.

In a step to address this, Fayetteville is engaging with the evolving practice of pre-approving buildings. While many elected officials, developers and residents are familiar with zoning as the primary regulatory tool for land use, “pattern zoning” is a less common standard. Pattern zoning creates a framework for neighborhood-oriented residential and commercial projects along with a convenient path to project approval. As a subset of pattern zoning, a pre-approved building design program uses stakeholder engagement, market study and ordinance research to craft a series of context-sensitive buildings for a given project boundary. These buildings are vetted for compliance with adopted codes and ordinances and then made available to residents and developers who can benefit from the savings in design cost, permitting time and, ultimately, risk.

For Fayetteville, a pre-approved building program can meet several goals, from reducing barriers to housing production and restoring municipal control over residential building design, to giving residents some agency over neighborhood appearance and giving the opportunity for incremental introduction of new, but appropriately scaled, housing types. Additionally, vetting building designs through the municipal review process is an opportunity to simultaneously evaluate internal processes. With development of the pre-approved building program still underway, expectations are high.

“All told, while Fayetteville has adapted in many ways to the housing crisis, data indicate that more change is needed. ”

With almost one-third of the city zoned for quarter-acre, single-family homes, zoning reform is likely an issue on the horizon. Similarly, development costs that Fayetteville can influence, like infrastructure requirements, fees and design standards, all merit consideration for whether they contribute to higher quality design and standard of living or if they are relics of 20th century best practices. If past efforts are any indication, Fayetteville will remain on its path toward methodical experimentation, deliberate change and steady progress.

Jonathan Curth, AICP, is development services director for the city of Fayetteville, overseeing planning, building safety and code enforcement.